In a recent interview (http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/feb/12/ballet-grand-dames-gillian-lynne-bery-grey-push-dancers-limit)

, Beryl Grey and Gillian Lynne, former Royal Ballet stars now in their

eighties, criticized the culture of contemporary ballet for coddling dancers,

for making them soft through such pampering treatment as nutritional

counseling, physical therapy, and rest days. Never mind that more dancers are

maintaining longer careers and retiring with mental and physical health intact

these days than ever in the past; these lionesses protest that they worked

longer days and longer seasons on starvation wages and were glad to do it. “Ballet

is hard,” they say.

|

| Beryl Grey |

I have immense respect for these women, who were indeed

tough-as-nails swans in their day; it takes a certain degree of fortitude to

compete with Margot Fonteyn. However, their griping is just more of that “in my

day, we had to walk uphill in the snow BOTH ways,” self-aggrandizement that

Saturday Night Live made such good fun of years ago. In fact, dance has changed

in ways that would make the hours they worked crippling and I find it hard to

regret that artists are now accorded the some of the same prerogatives as other

working athletes. I cannot imagine a retired NBA player decrying the fact that

players today have access to ultrasound therapy for strained muscles. And as

for the talk of dieting and the valorization of anorexia, I am sorry, but how

does being physically weak and mentally ill make you a better, more expressive

artist?

The athleticism of modern ballet also comes under fire from

Grey and Lynne on the grounds that dancers, though technically more skilled and

versatile today, are less “soulful.” Codswallop! This is another one of those

commonplaces rooted in cheap nostalgia and, I suspect, an insidiously

anti-feminist, class- and race- based set of expectations about the ballerina.

She should be delicate, pale, trembling, a veritable wraith (a Sylphide!).

Visibly muscular women, women of color, tall women, none of these have a place

in the Victorian imaginarium in which traditional classical ballet was for so

long invested. But more and more, the color of the ballerina, and along with

that, the range of acceptable body types, is becoming more open to difference.

This week, I am in Chicago, and I was able to sneak away

from the conference I am attending to see a performance by the Joffrey Ballet

at the historic Auditorium Theater, just a few blocks from the hotel. All three

works performed on the triple bill http://joffrey.org/contemporary

were of relatively recent genesis: Crossing Ashland, by Brock Clawson,

Continuum, by Christopher Wheeldon, and Episode 31, by Alexander Ekman. Each of

them had a distinctly different relationship to classical ballet, with Clawson closest

in his investigation of using the body as an emotional glyph to European

choreographers, like Jiri Kylian, Wheeldon typically hewing close to Balanchine’s

starker neo-classical idiom, and Ekman more kindred in spirit to Bob Fosse (if

Bob Fosse took speed and went clubbing in the 1990s). What all three works shared is that incredibly

technical and percussive athleticism that I have commented on before in writing

about contemporary ballet.

Ballet dancers today, unlike in Grey and Lynne’s time, are routinely

asked to use their bodies in a huge variety of very risky and unfamiliar ways,

hurtling through space, colliding with the floor, dragging and dragged,

stomping, falling… For example, in Ekman’s piece, the central pas-de-deux

involves two men in stocking feet, moving to a spoken-word recording of

children’s poetry that sounded like it was from the 1950s, and their

interactions compound martial-arts-like combat, contact-improv like rolls, and

lifts drawn from the classical repertoire, except made more challenging by the

fact that one is lifting a 150 pound man, not a 100 pound woman. Yet this

strange passage was, for me, the most compelling part of this odd, wacky

ballet; it got at the desire and the anxiety at the heart of ritual combat

(wrestling, boxing, dance-offs) between men while at the same time infusing

this potentially murky stew with a dash of peppery self-mockery. In other

words, it was emotionally, as well as physically challenging for the dancers.

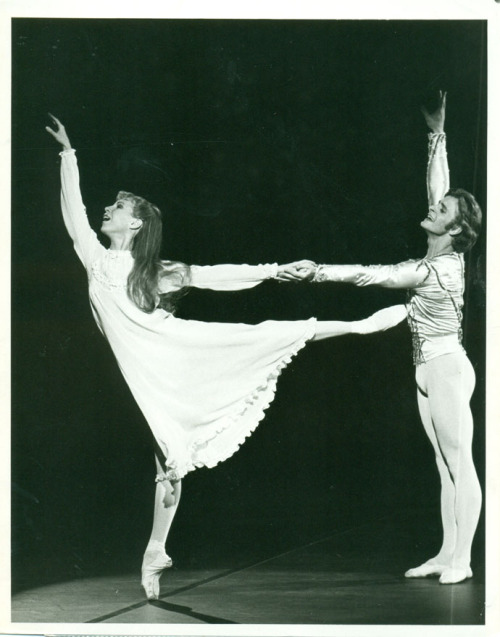

|

| Karel Cruz and Maria Chapman, PNB, in Wheeldon's After the Rain. |

|

| Barnett Newman, The Beginning, image from The Art Institute of Chicago website |

It is possible, indeed even probable, within the modernist

idiom of any art form, to tend toward a kind of dewy-eyed romanticism, and

Wheeldon is for me the dance-equivalent of Mark Rothko; deeply saturated fields

of emotional color thinned out and merging into dark tones around the edges,

the classical core breaking up into cloud-wisps, the light fading. Continuum, set to Ligety’s unrelentingly

modernist piano music, has the same structural rigor as a painting by Rothko,

or actually, more like something by Barnett Newman, that echt-technician of

Abstract Expressionism, whose 1946 The

Beginning I had seen earlier on the same day that I saw the Joffrey. It is,

like Continuum, both spare and lush. Oh yes, and it shares the same color palette.

If you take So You

Think You Can Dance as a gauge of “what dance has become” it is indeed the

case that athleticism and technical prowess have trumped the deeper, affective

and intellectual pleasures of the art form. However, that is a product of the

particular strictures of the television dance-competition form; those young

dancers (many of them no doubt deeply engaged with dance and capable of far

more reflective and mindful expression under other circumstances) have to learn

new choreography very quickly, and they are not given time to develop much of a

relationship to either the movement or the music, both of which are in any case

often vapid. Any "emoting" they do is very superficial and often tied to the uber-cheesy "lyrical" pieces set to pop ballads.

However, in real contemporary dance, athleticism is just one brush

in an ever expanding (and ever more physically and intellectually demanding)

quiver that artists are expected to bring to the studio. When you think about

the disconnect between the ballet training that most kids get in this country,

with its emphasis on traditional forms and technical mastery, and the feats of

imagination and strength that are asked of professionals in a company like the

Joffrey, the fact that dancers can identify and make visible the affective

qualities of the very difficult choreography they are asked to perform is all

the more impressive.

|

| "Bah, humbug!" |

Not all of them can do it. There was one dancer in the Wheeldon

piece who seemed too happy; she just grinned and beamed like a showgirl the whole

time and it drove me nuts since it meant she did not engage with her

pas-de-deux partner so much as with the audience. But that lack of emotional

sensitivity is in fact so rare among dancers I have seen in recent years that

it stood out.

In the end, as we age, we have choices. We can look at

what the world is becoming and marvel at it, try to wrap our minds around

the possibilities it offers, try to articulate the challenges it presents, and

try to stay relevant. At forty-five, no longer young but facing what I hope is

a long future of being not-young, I can only hope I have the courage to take

this route. Having spent a week at this conference where the up-and-comers in

my field look so bright and fresh and daring, I have had to be quite firm with

myself about singing that tired old tune of “Well, back in my day…”

And that is option number two: we can turn up our noses and sniff

about the inferiority of the moment in which we now live to the world of our

youth. There is nothing so repellent as an old snob.