In the past, I have written about ballet documentaries, a thriving genre of which there are many fine examples. But sometimes, one is in the mood for the escapism of narrative fiction. When you look for lists of top ballet films, very few of them are fiction; somehow, the two art forms seem to exercise a kind of anti-magnetism on one another.

However, I recently rewatched The

Turning Point, which is absolutely the best ballet movie ever. Ordinarily,

Shirley MacClaine is not one of my favorite actors, but in this film she is

absolutely brilliant as DeeDee, the early-middle-aged ex-ballerina who gave up

her career to raise a family in Oklahoma City with her husband, also former dancer

(played innocuously by Tom Skerritt). Her wistfulness, which I usually

find so annoying, is perfect; beguiled by the might-have-beens, she nonetheless

manages to keep a household running and provide some reasonable parenting to

her three kids. The main plotline has to do with her return to New York to

supervise the apprenticeship at the (thinly disguised) NYCB of her eldest

daughter, played by the ethereal (then) up-and-coming NYCB star Leslie Browne

and her relationship with her former bestie, who is still a principal dancer, played

by Anne Bancroft, with brittle but human grace. More than the plot, though, the

setting is what makes the film – I get such a distinctive sense of a New York

before Disneyfication and Giuliani made it a “safe” place for tourists, and the

developing independence of Emilia (Browne) is so touchingly limned. Of course,

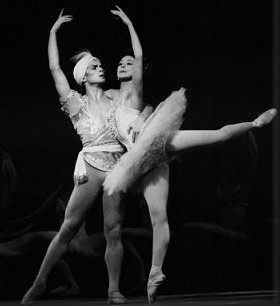

the very best part of the whole film is the transcendent scene where Emilia and

the predictably named Russian principal, Yuri (none other than a very young and

very beautiful Misha), rehearse that wrenchingly erotic pas-de-deux from Romeo and Juliet which then segues into

a love scene back in Yuri’s apartment. I mean, WOW, if you ever thought ballet

was stiff and formal, or that it glosses over sex, um, watch this. And then add

a chaser of Ingmar Bergman’s Summer

Interlude, from 1951, in which Maj-Britt Nilsson plays an older ballerina

reminiscing about a youthful love affair with the usual smouldering,

Scandinavian angst one expects from the great I.B.

|

| Ballet is hard (Summer Interlude) |

Most ballet movies in the narrative fiction genre leave me

pretty flat. Center Stage, which

often gets cited as “the best ballet movie ever” by people who obviously haven’t

seen The Turning Point seemed to me

just a jazzed up version of something you might see on Nickelodeon; teen

striving, teen angst, some catty byplay, a sympathetic gay black guy... give me

Dance Academy any day for character

development. In the same category of teen melodrama we might place Save the Last Dance (Julia Stiles,

racial tension, ballet vs. hip-hop); and Flashdance,

which is a bit grittier (just as the eighties were grittier than the nineties),

but basically the same story – girl wants to dance, girl is told she can’t

dance, girl dances anyway, and in the end she is a star and gets the guy. What

a feeling!

|

| Really? |

On the darker side, Black Swan, though it had its moments as

a psychological thriller, was a horror show as a ballet film; talk about

perpetuating the worst stereotypes about dancers and the world of dance while

exploiting cheap, vulgar-Freudian thrills in order to revel in the

victimization and self-destruction of yet another innocent, virginal young

thing. Also, there was this weird lack

of actual dance. File Dancers, the

1987 film with a similar plotline (dancers' lives parallel the plot of the

ballet they’re preparing, only this time it’s Giselle… starring Misha and Julie Kent, so some real dance) under

the same heading of “trite and exploitative.” Oddly, it’s by the same director

as The Turning Point, but the film

poster pretty much captures the cheese factor: Why does Baryshnikov look like an aged Luke

Skywalker here? Why?

Basically, both these films are remakes of The Red Shoes, in which life imitates

art and the ballerina does some kind of fatal (swan) dive at the end, ala Anna Karenina.

As much as I despise the boringness and

antifeminism of this plot, at least The

Red Shoes was great, even innovative filmmaking in its time; the color

(which has been restored) is lush, and the acting is hammy (it’s 1948 for

heaven’s sake) but also pretty lush. Moira Shearer is really lush (that red

hair!). And lushest of all are the extended scenes of original choreography for

the ballet within the film; who can resist all that mid-century modern

goofiness? Plus, the people who made the film were by and large pretty

well-versed in the ballet of the time… notice Leonide Massine there in the

cast.

|

| Vavoom! |

|

| Cinema verite. |

Robert Altman’s The

Company made a strong effort to portray the real psychological drama that

goes on offstage, and it also had more dancing of better quality than any of

the “demise of the dancer” psychodramas.

I love Altman – his McCabe and

Mrs. Miller is an all-time favorite of mine and also goes a long way to

explain Warren Beatty’s status as a sex-symbol in the 1970s. The Company was made as a close

collaboration between the Joffrey and Mr. Altman, and has a documentary feel to

it. Even so, in its fidelity to life it is actually a bit messy and dull,

despite a carefully understated performance by Neve Campbell as the heroine, a

young ballerina on the cusp of big success, pondering what this means for her

life. Similarly true-to-life in its content but less artistically sophisticated

is Mao’s Last Dancer, a bio-pic about

Li Cunxin, the Chinese-born and –trained principal for the Houston Ballet and

then Australian Ballet. It has some good dance footage, but by and large the acting

is a bit uninspired.

Then there is White

Nights, which I haven’t seen in years, so I cannot really critique it

except to say that the dance scenes are of course so fun to watch on YouTube (not

that that’s a regular, late night occurrence with me). Really, both Gregory

Hines and “I am in every movie made about classical ballet between 1970 and

1990” Baryshnikov are not at the top of their games anymore at that point, but

it doesn’t matter, because that’s sort of like saying that by 1985 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

was no longer at peak performance… true, but he was also MVP of the NBA finals

that year, which the Lakers won. Now I’m really showing my age. Ouch. Anyway I

sort of recall that the dynamic between Hines and Baryshnikov essentially

playing themselves was way more interesting than anything else that happens in

what is essentially a late-Cold-War stock narrative with a little racial

tension, a dash of Helen Mirren, a jigger of Isabella Rossellini, and a

top-forty hit by Lionel Richie just to liven things up a bit (say you, say me, say it together… that’s the

way it should be). Without spoiling the film for those of you who haven’t

seen it, let’s just say that it ends with everything “the way it should be” from

a 1985 Hollywood perspective. And what perspective is that, you might ask?

Well, among the top grossing films that year: Rambo First Blood Part II, Back

to the Future, Rocky IV, A View To a Kill, Pale Rider. U.S.A! U.S.A!

|

| He can jump. |

|

| So can he. |

One film that is not about

ballet but that has a ballerina as one of its main characters is the

not-so-spectacular sci-fi thriller, Adjustment

Bureau (2011), in which Emily Blunt plays a member of the Cedar Lake Ballet

involved romantically with a politician played by Matt Damon. In that film, the

fact that she’s a dancer is treated as pretty much equivalent to the fact that

he is a politician – both have demanding careers that involve certain

sacrifices on the personal front, and that require seriousness and a fairly

exclusive focus. I think more films in which ballet dancers are portrayed not

as swan princesses, cuckoos, or fainting maidens, but as serious artists who

are also real people might be nice.

Speaking of princesses, one might expect there

to be lots of ballet movies for the younger set, but there really aren’t. The

horridly adorable Emma Watson aka Hermione Granger starred in an adaptation of Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild

(written in 1936); the novel, for children, is of that dotty but delightful and

sneakily serious strain of British children’s literature. But it’s not really

about ballet – it’s about children in the theater business in 1930s London. Meanwhile,

Angelina Ballerina is a dancing mouse who made the grand jeté from books to

animated films, and when my daughter was much younger I am pretty sure we had a

movie starring none other than Barbie that purported to be a version of Swan Lake. Maybe there are others that I

just cannot remember or haven’t seen? Anyway, slim pickins.

|

| Anna Pavlova, 1912 |

It seems strange to me that the vast junior fiction universe

of ballet stories have not been translated onto the screen. A quick check of

GoodReads reveals an almost limitless virtual bookshelf of ballet-themed books

for young and old. Eva Ibbotson’s critically-applauded YA novel set in 1912, A Company of Swans, about the rebellious

daughter of a Cambridge classics professor who joins a touring Russian ballet company

that takes her to Manaus, where naturally she falls in love and all sorts of

drama ensues, now that would make a good BBC historical drama. I’ve heard

Julian Fellowes is leaving the helm of Downton

Abbey, so why not take this one on?

Sadly, I come to the conclusion that narrative fiction films

about ballet generally tend to disappoint. They get too maudlin about the

psychology of the artists, or they take too much pleasure in the spectacle of

the ballerina’s disintegration, or they merely drape ballet over a plot that

could just as easily serve tennis or motorsport. Often, they don’t bother to

show much real ballet. Of course, there are technical reasons for this; ballet

is difficult to film well: ballet dancers are not Hollywood stars (generally)

who can draw audiences to the theater to see a film: you can’t fake it when it

comes to portraying a ballerina (sorry, Natalie Portman, you are luminious, but

not a ballerina): ballet films are not going to appeal to the biggest

money-making audience sector, which is male and aged 14-25 or something about

like that. Also, it’s hard to imagine how you could turn a ballet film into a

violent digital game.

|

| But who would play Dame M? |

Still, I just want to throw this one out there. I would like

to beg Gillian Armstrong (the Australian auteur responsible for such films as Oscar and Lucinda and Mrs. Soffel, both must-sees) to pick up

Colum McCann’s

Dancer (see link on right) and cast Daniil Simkin in the Nureyev role. Now,

that would be a ballet movie worth its salt (and salty it would be).