A more somber than usual blog tonight, in memory of the

three human beings who lost their lives in the shootings in Kansas City on the

eve of Pesach. It would be disrespectful to their memory to call it mere irony

that none of them were Jews, when the gunman was a vitriolic anti-Semite whose

choice of venues was clearly motivated by his hatred of Jews, but it does

remind me of the famous lament of the German Protestant minister Martin

Niemöller, “First they came for…” Every time one of these crimes occurs, in

which the cocktail of readily-available arms, tolerance of sociopathy cloaked

as political opinion, and a twist perverted vigilantism, explodes into yet

another utterly shocking and yet predictable bloodbath, I think of how he

concludes his condemnation of his own and other’s indifference to Nazi

genocide: “and then, they came for me.”

What, if anything, this has to do with ballet, I do not

rightly know, though on Saturday I am going to see Ballet West perform Jiří

Kylián’s Forgotten Land, along with a

couple of other things (like, for instance, Rite

of Spring). Last fall I saw his earlier Return

to a Strange Land, a tribute to his own mentor, suddenly dead, set to

Janacek’s haunting cycle of piano pieces composed as a lament for his daughter,

and Forgotten Land (according tonotes on the Joffrey Ballet website) “explores memories, events, and people

that over time are lost or forgotten.” The echo of the title of the earlier

work cannot be a coincidence. Also, it is set to Benjamin Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem, which, while not as

heartbreaking as the Janacek, is nevertheless not a cheery piece of music,

taking as the implicit text of its three movements the Lacrymosa, the Dies Irae, and

the Requiem aeternam of Office of the

Dead.

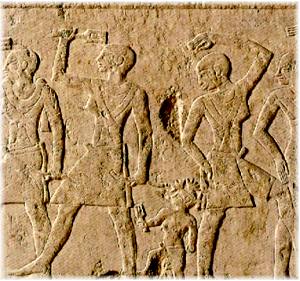

Dance and mourning are old partners; you can see them going

down the road together at any New Orleans-style funeral, or along the walls of

some old churches in Scandinavia, or following along behind the mummy in

Egyptian tomb paintings. The dancers may be sending the departed off in style,

celebrating the life lived, or using their living bodies in motion as a

talisman against the stillness of the grave.

There is no talisman, no Tau painted in the blood of a lamb,

that can spare any of us from the fate of all living beings – that is, to die –

but one can certainly imagine things we might do to lessen the risk that a

fourteen-year-old boy aspiring to compete in a teen talent contest and his

grandfather, a physician and a family man, would be shot by a former KKK

official armed with legally-obtained guns and an excess of perverted

self-righteousness (the guy was still shouting “Heil Hitler” when they arrested

him). One can certainly imagine laws and safeguards that would have helped

prevent the senseless death of Terri LeManno, who was visiting her elderly

mother at a Jewish-run retirement home (LeManno was Catholic). It may be true

in a limited and highly disingenuous way when NRA boosters say, that “guns don’t

kill people, people kill people,” but last week when a deranged teenager went

on a rampage at Franklin Regional High School with a pair of knives, nobody

died. A physician who treated some of the patients observed that if the boy had

been shooting instead of stabbing, the situation would have been far worse. So

people with guns do kill people much more effectively than people with sharp objects. It is one of the things guns are for and one of the reasons people no longer go to war armed "only" with spears.

So what to do, not to fall victim to quietism or despair? This

week, looking for some more socially and politically relevant way to celebrate

Passover with my kids, I came across an opinion piece by Rabbi Arthur Waskow, a

Jewish activist and Occupy Wall Streeter from New York City, that ran in the Huffington

Post in 2012. He proposes ways that people of different faith traditions can

enrich their celebration of the season’s holy days (Pesach and Palm Sunday), by

linking the ancient rituals to present day issues. It is pretty standard stuff

in terms of connecting the sufferings of the poor and oppressed today to the

fundamental messages of social justice that both Judaism and Christianity can

be understood to contain, but I really like way he concludes. He says that the

world is undergoing an “earthquake” at all levels, from the disruption of basic

biological systems to the technological redefinition of the self and

sociability, and that we have three choices; ignore the quake and get crushed

in the rubble, cling to the past as something immovable and become hopelessly

reactionary, or learn to dance in the earthquake. He urges us to “attempt to

dance in the midst of our earthquake.”

It is a metaphor, I know. But it is a metaphor with a

groove, and maybe we can dance our way out of this sad mess to it.