If one knows anything at all about the history of classical

ballet, one knows that it began, more or less, with the court dances of the

Ancien Régime, in France. In particular, Louis XIV, the brilliant young “Sun

King” while a still a teenager raised the art form from polite entertainment to

a shock-and-awe spectacle that made manifest his divine election. In 1653, at

the connivance of his Italian chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, he appeared in

a suite of dances called Le Ballet de la

Nuit, with music by Lully, culminating (as the night generally does) with

the break of day, when the king, dressed in golden armor of the Roman style and

sporting a corona of golden rays, “rose” from beneath the dancing floor, in the

persona of Apollo.

Gérard Corbiau’s film, Le roi danse, from 2000 is hard to get hold of in the US, but you can at least watch his reconstruction of the thrilling moment on

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BMvpvDjFvHA.

Aside from the slight whiff of fromage

it provides quite a convincing picture of how impressive this apotheosis would

have been.

|

Vaux-le-Vicomte: a pocket Versailles

(for those with deep pockets) |

And Louis took dance very seriously; in 1661 he actually arrested

(and subsequently imprisoned for life) his finance minister, in part because of

a ballet. Nicolas Fouquet had commissioned a work from

the great dramatist Molière, Les Fâcheux (“The

Unfortunates” or "The Annoying Ones" – a cruelly apt title given what became of its patron). It was

performed on a hot August evening in the gardens of his magnificent castle at

Vaux-le-Vicomte, and tout le monde attended.

The King was the guest of honor. He applauded Molière’s accomplishment, but he was

not amused by the pretense of his CFO. Fouquet had dared to rival the king as a

patron of both architecture and ballet – the means by which Louis perceived his

divine prerogative should be made manifest.

But why dance? It all has to do with power and message. The

dancer’s body speaks persuasively, viscerally, and that means that whatever

message it conveys exercises persuasive force. An absolute monarch absolutely

must control the messages that bodies in motion express. Mark Franko, a dance

historian, writes, “In 1661, court ballet was still a vast metaphor for social

interaction. In order to exert control over the medium of dance, which was

indirectly a control over his courtiers, he (Louis) institutionalized dance by

founding a Royal Academy of Dancing.” [Franko, 2015].

|

| He's got legs and he knows how to use them. |

Louis was the Dancing King, and the King of

Dance as well (and he had the gams to prove it, as his famous portrait by

Hycinthe Rigaud shows). Ballet would not be the same without him. But he was

not the only monarch to stake his power on dance performance.

Today I went to Dumbarton Oaks, a small

museum that specializes in Byzantine and Pre-Columbian art. The collection was

assembled by Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss, a wealthy diplomatic couple,

who gave their house (which they had designed with an eye to its future

existence as a museum), collections, and gardens to Harvard University in 1940

as “a home for the humanities.” It is a little corner of Paradise in

Georgetown.

|

| The Johnson Pavilion |

After spending a very long time ogling the

exquisite objects in the Byzantine collection (oh, the jewelry!), I wandered

into the new part of the building (the original house is a Federal-style brick

mansion); this addition was built by Philip Johnson in the early 1960s, and it

is, in true Johnson fashion, more glass and light and air than anything else.

It takes the form of a ring of domed pavilions encircling a simple fountain. I

overheard a woman saying, “Ah, still more beauty!” as she looked about.

In the pavilion dedicated to the Maya, I

eavesdropped while an erudite man explained to his companion the differences

between alphabets, syllabaries, and ideographic systems. It turns out that when

paleographers are trying to decipher an ancient form of writing, they use basic

statistical analysis to begin to understand whether they’re looking at an

alphabetical system in which each character corresponds to a single sound, a

syllabary, in which character represents a syllable (consonant/vowel grouping),

or a pictographic or ideographic system, in which the characters represent

whole words. It turns out (according to Mr. Smarty Pants, who sounded pretty

credible to me) that if there are about 20-40 frequently repeated characters,

you are looking at an alphabet, 40-70, a syllabary, and over 70, usually over

100, an ideographic system.

When he had moved on I walked over to see

what had prompted his little disquisition; and it was a limestone panel, about

six feet tall, dense, yes, with Mayan glyphs (which are a combination of

logograms and syllabic characters, as it happens). But at the center, almost

life size, stands a figure. Or rather, not stands, but dances. His body faces

front, though he turns his head sharply to the left, so his face appears in

full profile.

|

| For a zoomable hi-res image go here |

Young, lithe, and slim as any Greek kouros,

he also shares their suspension between aristocratic detachment and action.

He

lifts one heel off the ground, cocking his knee and raising his hip and

shoulder on that side. His corresponding arm also rises, his elbow just a

little lower than his shoulder, his hand held up at the height of his head, his

fingers curled around the slender, serpentine handle of his very nasty looking

axe (I had just been checking out the evil-yet-beautiful jade axe blades in the

neighboring vitrine). On the other side, he holds his hand low, by his hip, and

in it he clutches some kind of handled pot and a docile-looking viper.

According to the museum’s wall label, this little bucket is labeled “darkness”

and symbolizes a massive, light-killing thunderstorm.

The glyphs give us his name – K’an Joy Chitam – and inform those who

can read them that here he performs a dance in which he becomes Chaak, the

Mayan god of bad weather and blood sacrifice. His parents kneel to either side

of him, as the panel has some kind of genealogical significance.

He wears an elaborate costume. His head-dress,

ear-ornaments, necklace, and pectoral seem to be made up of serpents’ coils,

turtle shells, and beads. He wears cuffs with inlaid patterns that look a great

deal like the flashy golden arm-rings embedded with precious stones that I saw

in a case a few yards away. Then he has this pleated kilt of sorts,

high-waisted, falling just to the tops of his thighs, and close fitting, showing

off the trim line of his waist and the swell of his thigh muscles. Over this he

wears a belt with two enormous strap-work bosses over the hips and a long,

long, sash hanging down right in the center, pinched between two enormous beads

between his thighs, and then descending to the space between his ankles in

their striated cuffs.

I would guess that originally the panel belonged to some

tomb or temple complex built in honor of this short-lived king, and that it

would have been painted brightly (I’ve watched my share of documentaries on

Nova); but even isolated and bare, it conveys a sense of this muscular, lithe,

young deity in human form, using his rigorously disciplined body to bridge the

gap between this world and that of the gods.

Dance, like other art

forms, is instrumental; that is, it enacts, rather than just relates,

knowledge, states of being, and power.

Matthew Looper explains the function of dance in rituals of kingship in

the Classic Maya world thus, “Such displays did not merely represent rulers’

control over divine forces, but actualized this power, making it real through

aesthetically grounded experience” (Looper, 2009).

That the human brain has some intrinsic aesthetic capability,

similar and perhaps related to the capability for spoken language, has emerged

from recent neuroscientific research, so that perhaps now people will begin to

take seriously what humanists have been insisting ever since Kant (at least),

namely that aesthetic experience is substantive, real and powerful. Although I

cringe at any universalizing theory that seeks to put all humanity in one tidy

explanatory box, I would like to think that K’an Joy Chitam and Louis XIV would

have recognized themselves in one another despite the vast gulf of time, space,

and culture between them. For both, the body of the king in all its youthful

virility, its splendidly costumed pomp, its skillful, technical command of

precise movement, made real and present their special relationship to their

respective deities.

Perhaps Merce Cunningham said it best: “If a dancer dances –

which is not the same as having theories about dancing or wishing to dance or

trying to dance or remembering in his body someone else’s dance – but if the

dancer dances, everything is there. . . Our ecstasy in dance comes from the possible

gift of freedom, the exhilarating moment that this exposing of the bare energy

can give us. What is meant is not license, but freedom.” So maybe that is why the king must lead the dance... otherwise, people might think that freedom belongs to them!

To read more about the Dumbarton Oaks dancer:

Matthew Looper, To Be

Like Gods: Dance in Ancient Maya Civilization, University of Texas Press,

2009

For more on Louis XIV and ballet:

Jennifer Homans, Apollo’s

Angels: A History of Ballet, Random House, 2011

Mark Franko, Dance as

Text: Ideologies of the Baroque Body, Oxford University Press, 2015

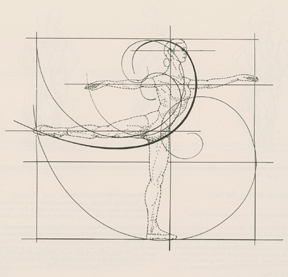

My one real reservation about most print ballet dictionaries is their puzzling lack of illustrations. Though some do have line-drawings or photographs (usually grainy, black-and-white), these are often less helpful than you might hope. However, there are exceptions to this: the Royal Academy of Dance has a book-version of its syllabus with good line drawings that can be quite helpful, while Lincoln Kirstein's Classic Ballet, with over 800 drawings by Carlus Dyer is widely thought to be the classic illustrated book. As the illustration here suggests, there is an element of Leonardo-esque idealism to the book. But all those swooping curves do make for fantastic visualizations.

My one real reservation about most print ballet dictionaries is their puzzling lack of illustrations. Though some do have line-drawings or photographs (usually grainy, black-and-white), these are often less helpful than you might hope. However, there are exceptions to this: the Royal Academy of Dance has a book-version of its syllabus with good line drawings that can be quite helpful, while Lincoln Kirstein's Classic Ballet, with over 800 drawings by Carlus Dyer is widely thought to be the classic illustrated book. As the illustration here suggests, there is an element of Leonardo-esque idealism to the book. But all those swooping curves do make for fantastic visualizations.