A recent whim led me to check out my page-view statistics

for this blog and I was totally surprised to find that people whom I don’t

actually know must be reading it, at least from time to time. This constitutes

a big change from six months ago when I was the only one who read it, ever. How

do I ascertain that some of you are strangers to me? By the simple fact that

some page views come from Russia, and so far as I know, nobody I know directly

lives in Russia.

|

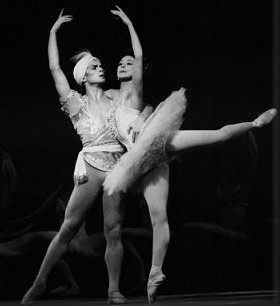

| The Bright Stream... one of the original "tractor ballets" now in revival. |

This is all a little intimidating. Not only am I a child of

the Cold War, for whom the ceaseless barrage of media-borne Russophobia of the

70s and 80s was a formative factor in my psychic development, but I am also

presuming to write about ballet, which, while hardly born on Russian soil, is

so clearly and definitely Russian in so many ways. Let’s add to this that my

maternal grandmother’s family fled a Russian pogrom of Kiev in 1881. And what

with the violent character of recent developments in the Russian ballet world (namely the acid attack on Sergei Filin of the Bolshoi), one does tend to get a little

edgy.

Russia, or rather the Soviet Union, was the most terrifying

bogeyman of my childhood. I know this will sound totally clichéd, but when I

was young, I lived in dire fear of total nuclear war. I grew up in Seattle, and

the flight paths for SeaTac airport sometimes went right over our house; at

night, I would lie in bed and listen to the jets, very certain that someday

soon one of them would not be a plane at all, but a big ICBM coming to kill us

all in the interest of wiping out the nuclear submarine base on Puget Sound. I

had seen, in Life Magazine photo books in the school library, the horrific

images of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and those were the visions of

sugarplums that danced in my head.

|

| Yeehaw! Mutual Assured Destruction! |

At the same time I was aware of another Russia, the Russia

that produced the divinely beautiful Misha and my heroine Natalia Makarova, the

Russia of The Firebird, and the

Russia of The Children of Theater Street.

That Russia fascinated me and seemed a dream country. Russian literature, I

understood from Woody Allen, was both heavier and more easily lampooned than

western European literature (oh, how I still love Love and Death, which I laughed at long before I ever picked up a

novel by Tolstoy or read a short story by Chekov: "Your skin is so soft!" "Yes, and it covers my whole body."). Russian women, I knew from

James Bond films, were more beautiful and sinister than American women.

I even

had real-world evidence for this last point. A girl who went to my middle school, Lara,

was Russian – her family had defected, not all that long ago. It was a very

romantic story, though I don’t recall the details. Lara was absolutely

gorgeous, with one of those cut-yourself-on-my-cheekbones faces, thick hair the

color of actual, real gold, and the most stunning blue-green eyes. She was also

very physically developed and I remember all the boys panting around after her

like, well, like lust-crazed thirteen year old boys.

Plus, her name was Lara.

|

| Lara, aka Julie Christie. Not Russian. |

I had one of those music-box jewelry boxes that were popular

at the time; some kind of printed vinyl paper exterior, flocked pink velvet

lining, and a little plastic ballerina with a tutu made of real tulle who

rotated slowly while the music played. It had the theme music from Dr. Zhivago. I used to dance around in

my room to it, because I thought it was actually Russian ballet music. Years

later, in high school, when my Italian friend Elisa, a film buff, dragged me to

a showing of Dr. Zhivago at the

Neptune, I was shocked to discover that in fact Tchaikovsky had nothing to do

with it. Really, there’s nothing very Russian about it all: Julie Christie, who

played Lara in the film, was born in Assam, India to English tea-planters; the

composer, Maurice Jarre was French; the MGM Studio Orchestra, which played the

soundtrack music was not particularly Russian, though the balalaikas on the

soundtrack were evidently played by musicians from the Russian Orthodox

churches around L.A.

|

| Pussy Riot in action, 2012, Red Square |

To my youthful imagination, Russia was at once this menacing

beast that threatened to eat us all alive, a hotbed of sinister spies, an

exciting foreign place where people rolled their R’s, wore fur coats, and ate

caviar on rye toast in their dachas, and the font of all that was truly

inspired in classical dance. Now having

grown up and living in a world where Russia figures very differently in the

geopolitical game, I have (I hope) acquired a more subtle and complex

understanding of “Russia.” I’ve read more of the great Russian books (even

without Woody Allen, there’s quite a lot of humor there), forced myself to sit

through some of the more bloated classics of Russian cinema (is there a medal

for watching all of Andre Rubelev with

sporadic Italian subtitles?), followed the unraveling of what looked like an

impulse toward a more open society in the early 1990s, worried about the

long-term consequences of Putin’s policies in Chechnya and elsewhere, and

shuddered at the excesses of the criminal aristocracy (plus ca change?) and the

murderous persecution of artists and journalists.

Still, my “Russia” is a

Russia of the imagination; I’ve never been there, and I have few contacts with

Russians (aside from a few friends and colleagues, who belong to that subset of

Russians who are also

|

| Features Madame Snezhnevskaya, ballerina and royal mistress |

I have never seen the Bolshoi or the Kirov live on stage. I’ve

never seen any of the current crop of Russian born or Russian trained stars. I’ve

seen Baryshnikov, yes, but dancing José Limon’s choreography, nothing Russian.

I watch a lot of Russian ballet on YouTube, but really, we all know that’s not

the same. So let’s call this a disclaimer; I am a serious ballet lover who

lacks any stamp of Russian authenticity.

|

| A serf ballerina, ca. 1800 |

Whoever you are reading this, out

there in the fatherland of ballet, I salute you and I honor the great tradition

of classical dance in Russia as it is today, as it was under the Soviet Union,

and back in the old days, when noblemen kept serf ballerinas in their

Petersburg town-homes and pet foreign ballet masters at their beck and call. May

you live long and attend many performances at the Mariinski.

Dasvidaniya!

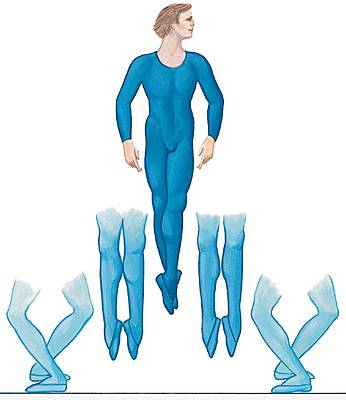

fouetté

movement

fouetté

movement